Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Introduction

If you have been following my Sub 12-minute two-mile challenge, you will know that most of the discussion so far has focused on cardiovascular limits like LT1, LT2, and VO2 max. Those systems matter, but as my pace increased, another set of constraints became impossible to ignore.

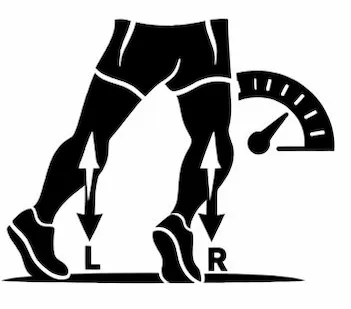

Alongside faster splits, I began noticing lower back dysfunction, subtle knee irritation, and unwanted torso rotation. These were not conditioning problems. They were stability and coordination problems. This post is a companion to the Sub-12 series and focuses on the physical adaptations I have been working through, specifically restoring symmetrical force production through the hips using concepts from Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization and the McGill Big 3. The goal was not more strength, but giving the nervous system enough stability to stop limiting force output during faster running.

The core principle I’ve been following is this: insufficient hip and trunk stability causes the brain to restrict force production. Regaining stability through specific training methods, Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS), the McGill 3, and resistance work, restores lost force and improves running form. Though my progress is ongoing, early results stand out: knee pain resolved, running feels balanced, and race pace is rising.

Mental Protection vs Force Production

The nervous system prioritizes protection over performance. After injury, this is obvious. What is less obvious is when protective strategies become chronic even after tissues are healed. In running, this often manifests as reduced push-off, an asymmetrical stride, or excessive trunk tension at higher speeds.

For me, this protection showed up as an inability to sustain a six-minute mile pace. After about 90 seconds, my lower back would tighten, and maintaining form required conscious effort. Multiple short intervals at this pace reliably produced next-day soreness in stabilizing muscles rather than prime movers. This suggested that force was being limited upstream, not that my legs lacked strength.

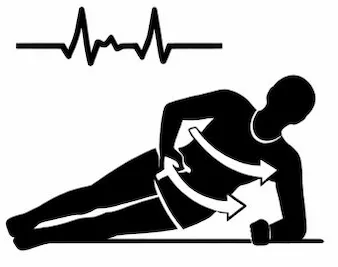

The McGill Big 3

The McGill Big 3 were the first stability-focused exercises I consistently practiced. The goal of these movements is not to build maximal strength, but to create sufficient spinal stiffness so that the force generated by the hips can be transmitted without loss or compensation.

The three exercises are:

- A modified curl-up (an abdominal exercise done with feet on the ground and minimal trunk flexion),

- A side plank (a pose that supports the body on one forearm and the side of the foot), and

- The bird dog (an exercise where you balance on hands and knees, extending opposite arm and leg).

Together, they train trunk endurance and coordination while minimizing spinal motion. This model treats the spine as a structure that must stay stable so the limbs can work.

After starting the McGill Big 3 each morning, I noticed less lower back pain while running. Though my spine felt more stable, my left side remained weaker, and propulsion remained uneven. This led me to incorporate targeted gluteus medius (the muscle on the side of the hip, important for hip stability) work alongside the McGill Big 3 core exercises.

Resistance Exercises

After some experimentation, I settled on exercises that focused on frontal-plane (side-to-side) hip stability and single-leg control. The intent was to reduce pelvic drop and rotation so each leg could contribute force more evenly.

I first learned about Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS) through the DNS Star movement exercise, which led me to explore further DNS movements. DNS focuses on improving movement and posture by enhancing core control and joint stability, and now guides how I choose and perform my exercises. I expand on specific DNS movement patterns in the next section.

Building on the DNS approach, my next exercise is the Hip Airplane. I like this exercise because it highlights differences in motor control between my right and left hips. My right hip has better motor control, so when I train my left, I focus on matching it. Improvement isn’t noticeable in a day, but over weeks and months, the left hip grows stronger and more stable.

My final exercise involves alternating between the banded side shuffle and the single-leg gluteus bridge. I complete one set of the banded side shuffle, then immediately move to a set of the single-leg gluteus bridge, and repeat this pattern. For both exercises, I perform repetitions until I feel a burn in the gluteus medius, indicating the muscle is activated and functioning well.

This mix of drills brought concrete gains: pain disappeared, form improved, but at high speeds, bracing took effort. This revealed that spinal stiffness alone could not fully free up symmetrical force production. My search for other movement patterns led me to research DNS.

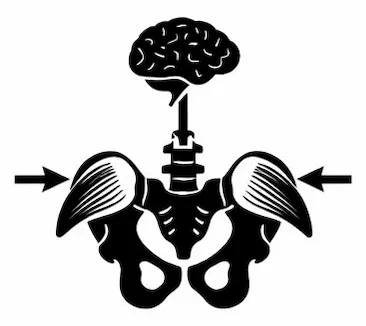

Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS)

Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS) is based on predictable movement patterns that develop in infancy. These patterns involve coordinated activation of the diaphragm (the primary muscle for breathing), the abdominal wall (muscles supporting the front and sides of the torso), the pelvic floor (muscles at the base of the pelvis), and the hip musculature (muscles around the hip joint). DNS assumes these movement patterns remain accessible throughout life and can be retrained if movement quality declines.

DNS exercises often use developmental age labels, like 1-month, 3-month, or 5-month positions. Early prone positions build head control and trunk stability before allowing limb-driven force. The order matters: stability first, then movement.

DNS shifted my thinking: if trunk and hips lack stability, the nervous system cuts leg drive to protect the lumbar spine. This matched my years of reduced left-leg force, leading to compensation and inefficient running.

With DNS-based drills, I began restoring symmetrical hip engagement without changing my running. Over time, the sensation of bracing decreased while usable force increased. This was not a traditional strength gain. Instead, it was the removal of a protective constraint.

References

Link to McGill Big 3 reference material https://youtu.be/2_e4I-brfqs?si=7JdfU0LJJ0XM3HBS and https://youtu.be/_TKMVfEKDlM?si=e0mGSlCoQHFUi9iW

Link to Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabalization https://wikimsk.org/wiki/Dynamic_Neuromuscular_Stabilisation

Link to Reflex Locomotion Stimulation https://wikimsk.org/wiki/Reflex_Locomotion_Stimulation